Flutesong Over The Water

On family, memory, cricket, tea, and India.

Flutesong Over the Water

published in WISDEN’s the nightwatchman, ISSUE 27 (AUTUMN 2019)

All air, all sky shudders

with that flutesong over the water

Alas

My boat must be sailed now

It’s getting too late to wait on the shore

Alas

My boat must be sailed

– Rabindranath Tagore, Gitanjali

It was a crisp morning in May of 1941 when my grandfather’s cricket match was called off. He was at the crease – I picture it as stubbly but neat, the wicket at Swanage Grammar School – when the headmaster came striding out, waving his arms. Someone must have heard it come through on the radio: the pride of the British navy, HMS Hood, had been sunk. 1,415 British naval men were drowned. The previous year, in faraway India, Mahatma Gandhi had declared that people should not “countenance such amusements” as cricket “when the whole of the thinking world should be in mourning” over the global slaughter. Presumably the headmaster of Swanage Grammar School harboured similar feelings, thought it bad form to indulge in games in the wake of such tragic death.

As he trudged back inside, a knackered school bat tucked under his arm, my grandfather – Roy – was 15. His home was a farm named Wilkswood, nestled in a rolling, half-wild corner of Dorset so placid that to this day you can hear birdsong at any hour. The family milked cows or made hay year-round, mumbling hymns on a Sunday. In his boyhood, cricket was probably the most exciting thing in my grandfather’s life – the woodslap echo of a man with a sizeable paunch but a good eye middling one into the long grass. By 1940, though, the Hardy-esque tranquility had evaporated. War was here. All three of Roy’s older brothers had signed up for the RAF, and nine months before the HMS Hood went under, the oldest, Dick, was taking to the skies during a training exercise at Stradishall in Norfolk when his bomber lurched to starboard and crashed in flames. Dick was 31. Down the years, the family account was that he had perished in the Battle of Britain. Fair enough.

The teenage Roy, then, was well aware that his country was at war. With some regularity, on their return from bombing raids of Liverpool and Birmingham and elsewhere, yellow-nosed German planes swooped over the Dorset coastline to empty their remaining ammunition into its tranquil fields. At school, Roy carried a gas mask in a box around his neck. To the south, the tiny cliffside hamlet of Worth Matravers was acting as the nerve centre of British early-warning radar development; the 360-foot tower was visible from the family farm.

"With some regularity, on their return from bombing raids of Liverpool and Birmingham and elsewhere, yellow-nosed German planes swooped over the Dorset coastline to empty their remaining ammunition into its tranquil fields. At school, Roy carried a gas mask in a box around his neck."

For the Nazis, sport was about one thing: shaping young men into Discobolus-esque specimens whose athletic prowess would translate into victory on the battlefield. Hence Hitler hated cricket, believing that with its leisurely pace and only sporadic exertions it was “unmanly and un-German”. Call it a quiet sort of up-yours, cricket persisting throughout the villages of rural England even as the jackboots pounded. In 1941, through the window of a London-bound train, a refugee from Vichy France observed “all along the line young men in flannels... playing cricket in the sunshine on beautifully tended fields shaded by oaks and poplar trees”. My grandfather went on playing. This was that sepia age of cricket when there were no helmets, no limited-overs games, no ramp shots; when the players only ever wore white, and it was still seen as unsporting to appeal with too much zeal.

A few months after he turned 18, a recruitment fair was held in Swanage. Roy and his best friend walked the two miles. Clustered around tables heavy with free tea and cake were teams of rock-jawed men in full uniform, invoking a heady mix of adventure and moral crusade. Decades later, Roy would tell his daughter, my mother, that he and his friend had been tempted by both the Gurkhas and the Royal Marines. The Marines would mean just across the water, the Gurkhas would mean the other side of the planet. Eventually, Roy and his friend tossed a coin. The Gurkhas it was.

He didn’t wait to be conscripted. Why the haste? Was his patriotism enflamed by the flood of posters declaring “Britain Shall Not Burn” and “Your Britain: Fight For It Now”? Did he wish to avenge Dick’s death? Or was it just a way to escape sleepy Dorset, get the pulse going, witness outlandish things? Whatever his reasons, Roy signed up. By this point, the local mood was feverish. The Dorset peninsula offered the shortest sea route to Normandy, and thousands of Allied troops were amassing in and around Swanage. The American accents were an unprecedented exoticism. In April of 1944, a nearby strip of coastline played host to Operation Smash – the largest live-fire exercise of the war, a full-blown D-Day dry run attended by King George VI, Churchill, and Eisenhower. Roy was still waiting on his papers when the real D-Day came around. People read about the slaughter and the victory in newspapers delivered a day late, by the local vicar, on his bicycle.

A couple of months later, his commission came through. The 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles. It was real now – a stroll into Swanage, the toss of a coin, and here it was. On the eve of his departure, how did the family say farewell? Had they stockpiled meat and cheese rations ahead of a last feast? Was there booze? Did anyone say a few words? Whatever the nature of the goodbyes, the waiting was over. In October of 1944, Roy’s father – himself a veteran of that earlier war, the war that the people in charge had said would end all wars – watched his fourth and final son go off to fight. A slow, lonely bus to Southampton, and then at 18 years of age, having never travelled further afield than Somerset, Roy boarded a ship bound for Bombay. In the era of the Raj, it was said that colonial Brits, oppressed by the heat and the disease, tended to last for two monsoons. My grandfather would stay in India for 40 years.

According to the historian Ramachandra Guha, British sailors were playing cricket on Indian soil at least as far back as 1721. For a hundred years, though, India’s colonised indigenous people were sceptical. As a forgotten author named AG Bagot put it in 1897, the Indian natives were “apt to look on a cricket match as proof of the lunatic propensities of their masters... and to wonder what possible enjoyment they could find in running about in the sun all day after a leather ball”. Gradually, this changed. In Bombay, in the 1830s, Parsi boys began imitating the white man’s strange game, “their chimney- pots serving as wickets and their umbrellas as bats in hitting elliptical balls stuffed with old rags and sewn by veritably useful cobblers” (in the words of another Indian historian, Shapoorjee Sorabjee). Within three generations, training dusk till dawn on the Bombay esplanade, these local boys were reinventing spin bowling and beating English touring sides at the game believed, in the motherland, to be quintessentially Anglo-Saxon; rather beyond the reach, in psychology and sensibility, of brown folk.

My grandfather’s boat docked in Bombay’s Front Bay on 29 November 1944 – the day of his 19th birthday. A few miles from the port was that very esplanade where, a century earlier, Indian cricket had slowly been born. It was there, in 1926, that CK Nayudu smashed an English attack all over the ground, announcing Indian cricket’s arrival with a hailstorm of boundaries. It is doubtful, however, that my grandfather had cricket on his mind when he walked down the gangplank to a swirl of impossible impressions: women wrapped in whirlwinds of rainbow cloth; cows painted and ribcage-skinny; statues with elephant heads; the air thick with the smell of turmeric and rotting bananas. The glimmering jewel in the slipping crown of the empire. India – bigger than fifty Dorsets, hotter than ten suns.

Roy completed his Gurkha training at Abbottabad – famous today for being where Osama bin Laden was gunned down – and joined the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles, formed largely of Nepalese men famous for their ferocious warrior spirit. While here, according to his military records – stored under lock and key to this day, in the Asian & African Studies Reading Room of the British Library – Roy carried out “basic jungle training”: maintenance of a Sten gun; how to fashion a bamboo shelter; how to tell the difference between your phial of water steriliser and your phial of laxative. Lots of bayonetting mannequins. With impressive swiftness, Roy acquired “basic Gurkhali” and “basic Urdu”. At some point, as a Gurkha, he would have been equipped with a vicious, heavy, beautiful kukri knife. Decades later, stood in his Southsea flat at the age of ten, I would pull the knife from its frayed leather sheath, hold it in my soft hand, and think it surely too heavy for this old man – my grey- haired, stooped-back, trembling-hand Grandpa – to have ever wielded.

In mid-June of 1945, Roy and his regiment shipped out for Burma. Six weeks earlier the cricket-hating Hitler had blown his brains out, but on the other side of the world no one gave a monkey’s about Hitler. There was still fighting to be done; the Japanese wouldn’t accept that they were beaten. In 1917, Siegfried Sassoon had perceived in the ruined landscape of northern France “something in the sober twilight which could remind me of April evenings in England” and the “cricket field where a few of us had been having our first knock at the nets”. Nothing about Burma would have reminded my grandfather of Dorset, or of village cricket. Bamboo hard as bone and tall enough to blot out the stars; the rain coming down like an upturned ocean; mosquitoes plump enough to make a stain when squashed. Every night the men sizzled the never-ending leeches off their feet with cigarette butts and forced down gag-inducing mepacrine tablets for the malaria, even though they’d heard the pills made you impotent, made your hair fall out. Shark liver oil for strength. Where there were horses, the vets had to sever their vocal chords, and so the animals just gazed at you, drenched, moon-eyed. The men lay in an enforced silence through the dark hours; even rolling over was strictly prohibited.

"Nothing about Burma would have reminded my grandfather of Dorset, or of village cricket. Bamboo hard as bone and tall enough to blot out the stars; the rain coming down like an upturned ocean; mosquitoes plump enough to make a stain when squashed."

In the end, my grandfather was lucky: he arrived late, and his war lasted just seven weeks. Narrowly missing some horrific fighting at Kohima and elsewhere, his company spent their time crawling east, sporadically “mopping up” (as the regimental records put it) the retreating, defeated, destitute “Japs”. According to his commander, who wrote a letter to my mother when Roy died in 2004, his company had a mere “three brushes with the enemy – all showing signs of starvation and in rags of uniform”. Their main job was to keep a rough count of how many bloated Japanese bodies floated by on the River Sittang. The count is there, in pen and ink, in Roy’s war diaries: 100, 102, 151, 181, “100++”, 120.

And then, one sweltering morning, heart of summer in the jungle of Burma, news of Hiroshima and Nagasaki came through on the camp radio, and that was that. The war was done. All the brandy rations went out in a single evening. Roy’s regiment found its way to Rangoon, and then on to Bangkok. There were victory parades, and clean clothes, and fresh mangoes, and the forgotten, luminous sight of women. Roy was amazed at the American soldiers’ plentiful rations, particularly their copious cigarettes. Bangkok was full of Australians; some improvised games of cricket were played in the street.

After the war, my grandfather volunteered to stay and oversee the “internal security” associated with Partition; it is here, in the confusion of relinquishing a colony, that his British war records abruptly end. There is nothing on where he was stationed during Partition, what he did. But recently, over a lunch in Calcutta, an old and dear friend of his told me that my grandfather was in Punjab. Roy was a private man but once, after a Scotch or three, he told my father (his son-in-law) that it had been a horror: the trains, the massacres with machetes, the vultures and dogs feeding on the bodies, the not nearly enough men to stop any of it. Even after this, he stayed.

In 2011, my girlfriend and I took a 58-hour train from Mumbai to Guwahati, the capital of Assam. We dozed through miles and miles of flat, hot landscape, alighting at tiny, dusty stations to drink chai and be stared at. At night, by headtorch, I read a copy of William Radice’s translation of Tagore’s Gitanjali – pressed into my hands by my mother at Heathrow. Assam is way up there in the northeast of India, tucked behind Bangladesh and bordering Bhutan. Drive a few hours and you’re in the Himalayas; the next-door Indian state (Arunachal Pradesh) China partly claims as “South Tibet”. The language here is a long way from Hindi. The people are beautiful, in that way that people living near mountains always seem to be beautiful. I took this long train to Assam in 2011, and returned again this year, because it was in Assam that my grandfather made a new life, and a new family.

"I took this long train to Assam in 2011, and returned again this year, because it was in Assam that my grandfather made a new life, and a new family."

If you’ve ever heard of Assam, it’s probably because you’ve heard it mentioned in the context of tea, perhaps seen the word emblazoned across a dark red box of Twinings. The last two centuries of Assamese history are defined by the tea trade. Initially, that rapacious pseudo-state, the East India Company, ignored the region. Assam was miles from anywhere, and it was notorious for its dark religious practices that even now still see the occasional human sacrifice make the news. The place was all dense and sweltering jungle; it was teeming with fever and tigers; and it was surrounded by mountains that various unruly and marauding tribes called home. Though “the Company” was enthusiastically plundering nearby Bengal, Assam remained largely undisturbed.

And then, in between bouts of malaria, thanks to some local tribes who had been eating it for centuries, a handful of Brits living in Assam “discovered” tea growing wild. For a century, British merchants had been wanting to produce tea in British-owned soil, rather than be forced to buy it from Chinese merchants, at a mark-up, using silver they could only acquire by flooding China with opium. And here it was, growing wild in a corner of the Raj.

The “Tea Rush” of the 1830s began with young men who traipsed up the shifting sandbanks of the Brahmaputra into deepest Assam to live briefly like something out of a Conrad story – enjoy a fragile and lonely life of servants and easy shooting, eke out a few harvests, then succumb to alcoholism and the mosquitoes while the five months of drowning monsoon trapped you indoors. But over the decades, imperial capitalism took over, and tea revolution. Assam’s wild forests were hacked down to make room for vast plantations of lush, regimented tea bushes. These plantations, then as now, enabled Brits of all classes to drink tea all day long for a pittance. The self-sufficient Assamese refused to do the monotonous labour of tea-picking for a few rupees a day, so thousands of labourers were imported from hunger-stricken regions like Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. For a century, the working conditions were horrendous, an indentured servitude blighted by squalor and disease. The crop yields were huge, and so were the profits. Within a few decades, following one of its more forgotten colonial cruelties, Britain ruled the tea trade.

In the ’40s, even as the sun began to set on the empire in a multitude of places, companies largely indifferent to who held the reins in Delhi continued to print rupees, and the old boy networks that passed for HR departments continued to operate as they always had. In the months following Partition, probably sat under a bar-room ceiling-fan, probably in Calcutta, my grandfather bumped into someone who worked “in tea”. (At this time, the industry conducted something of a recruitment drive, aimed at the recently demobbed.) By July of 1948, Roy was on the books at McLeod Russel, the biggest tea-growing company in the world. Picture him: sweltering, two suitcases, boarding a propeller plane for Assam, not far from that stretch of wartime jungle he was probably still trying to forget. Perhaps he thought it would be a brief sojourn. But Assam would be his home for most of his life. He managed a variety of tea gardens, but closest to his heart was an estate called Monabarie, where he oversaw more than a thousand hectares of tea, and where his only daughter – my mother – was born.

The first cricket club outside Britain was founded in 1792 in Calcutta – like Bombay a port and hub of administration which had a heavy British presence, and thus bats and balls. The game was popular in the city, especially with gentrified Bengalis. (Cricket was “one of the languages of the Raj,” writes historian Richard Cashman; in the cynical view, upper-class Indians only started playing the game to get in their masters’ good books.) Assam was and is a long way from Calcutta, or indeed any of India’s cricketing heartlands. At the time of writing, the state has never produced an Indian international (though this could be about to change, with the emergence of the promising teenager, Riyan Parag). But still, cricket found its way to Assam, the same way it found its way across all of India: at the liver-spotted hands of homesick Brits desperate to play their boyhood game. In Assam, it was dragged from Guwahati out into the countryside by those dislocated Brits pacing up and down the tea gardens in floppy sunhats. Lawnmowers shipped upriver to mow the grass; all Kashmiri willow; local teak for stumps; balls stitched from the leather of a water buffalo.

As Guha reminds us, when India achieved independence, many nationalists “called for the game to disappear along with its promoters, the British”. These nationalists viewed India’s love of cricket as a sort of sublimated servitude, and aspired to make traditional Indian games like kabaddi the national passion. As we all know, these nationalists failed spectacularly. Indians fell head over heels for cricket. In Assam, a cricket association was formed in 1947, and a regional side played their debut first-class game the following year, in beautiful Shillong. A full roster of league sides quickly emerged. In the beginning, the teams carried the echo of Assam’s recent history: eight or nine Assamese guys, captained by a British planter with expensive pads and spotless whites. Over time, the planters would vanish. As in Bengal, Assam’s cricket season was short, owing to the heavy rains, and the wickets were spongy and slow.

In his early years in Assam, my grandfather dedicated huge amounts of energy to maintaining the best possible reception on the BBC World Service. This involved complex networks of homemade aerials that were rainproofed using banana leaves. Roy followed the Test series, and always kept an ear out for Somerset (he was born in Frome, and Dorset have never achieved first-class county status). Through the ’50s and ’60s, in a punishing, most un-English humidity, he played in the planter’s teams. He opened the batting, and also (I am told) tended to be first through the doors of the club bar at stumps. His first wife – today lost to Alzheimer’s in a nursing home, her memories of all of this melted away – was a punctilious scorer. The 1962 season was rudely interrupted by the month-long Sino-Indian War, when Chinese troops marched into Assam. Roy was tasked by the military with evacuating the whole tea-planting community – that is, the white-skinned slice of the tea-planting community – down to Calcutta. Roy retired in 1986, the year I was born, making him quite possibly the last British tea-planter in all of north-east India. He was pushing 60, and despite a worsening case of cataracts, continued to umpire, squinting and half-guessing at leg-before appeals.

"In his early years in Assam, my grandfather dedicated huge amounts of energy to maintaining the best possible reception on the BBC World Service. This involved complex networks of homemade aerials that were rainproofed using banana leaves."

Among all this, there is a knot of contradictions to my grandfather’s story. Despite his rather Raj-esque setup, he wasn’t posh. He lived posh: bungalow full of wicker chairs, bearers bringing tea to his bedside, evenings spent drinking gin at the club. The first woman he married, my grandmother, was very posh indeed – prone to condemning the macaque monkeys that crawl all over the tea estates as beastly or frightful. But my grandfather grew up squeezing udders, like his father, and his father’s father. He was a million miles from those Victorian Raj governors who would be royally miffed when a famine in the province they were meant to be overseeing forced them to cancel a cricket match. Roy wasn’t even like many other post-Raj planters, who often came from the oldest of old money.

Indeed, in my haphazard oral research, I have discovered that many of the other Brits saw him as something of an oddball. He spoke all the local languages, even those of the hill tribes; he adored Assam’s traditional music and poetry; he would walk down to the village for every big puja; and he would vanish upriver for days on fishing trips with local friends. Though he had a cook and a driver who called him sahib, he was also godfather to their children, he regularly bunged them sizeable cash bonuses, and they were distraught when he left. At Monabarie, his main tea garden, he diverted so many company funds toward building a school for local children that it almost got him fired. During rows, my grandmother would accuse him of having “gone native”.

And though her accusation has a colonialist ring, in a sense my grandmother was proved right. Roy’s second wife, Bina, was Assamese. He first encountered her at the festival of Bihu, where she was dressed as the Hindu goddess Radha. Her father was from Orissa; his parents had arrived as imported tea labour. He was a senior clerk at Monabarie. Bina was a tea-picker. Her relationship with Roy began during his final decade in Assam, and it is the reason I have ever set foot in this faraway corner of India.

When I first met Bina, my grandfather had been gone from Assam for 23 years, and resident of the great pavilion in the sky for seven. Bina’s house is a long drive from Assam’s main airport in Guwahati, up through flat miles of rice paddies, along long stretches where arrow-straight teak trees on the edge of bloom throw the car into shade. To the north, vague in the mist, are the hazy shoulders of the first Himalayas. The swastika – a pure-hearted symbol of Hindu divinity for centuries, before Hitler sullied it forevermore – is dotted everywhere. Out here, you are a great distance from cricket’s evolutionary roots (the ground close to my home in Bristol, for example, where WG Grace scored 13 first-class centuries). Nearby is Kaziranga National Park where, through ancient binoculars, my girlfriend and I watched a family of golden langurs feast on jackfruit. Driving into central Assam you go through miles of plantations, and the tea-pickers are still there now: all women, swaddled in saris, with enormous baskets strung on their backs, working their sinewed hands: top bud and two young leaves, top bud and two young leaves. I watch them and I am guilty, even though my guilt won’t help them, even though all birth is a fluke.

Bina’s house is lovely and spacious, cool stone floor and fabrics hung in the doorways. It is the very same house where she and my grandfather lived together, 30-odd years earlier, after he retired from tea. On my first visit, Bina had Roy’s military photo on a little shrine of sorts, with white petals garlanding the corners of the frame, and incense sending up coils of spicy smoke. Bina held my face, which I am told resembles Roy’s, and said his name like a mantra while tears ran in wrinkles down to the corners of her smile. She embraced my girlfriend, overflowing with love for her too, because family is family. Also present were her and Roy’s two sons, Robin and Sanju. Bina speaks little English, but theirs is impeccable. They translate, constantly. They are good men: honest, shockingly generous toward me, fiercely loyal to their mother. Both of them are good cricketers. Sanju works in tea.

He left them. When the boys were eight and six, my grandfather left them. Departed the house at sunrise, boarded a plane in Calcutta, and never set food in India again. There are conflicting accounts of his departure, all of them coloured by the mists of memory and time and personal loyalty. This wouldn’t be the place to parse or debate them. But even the kinder accounts, the accounts that make the abandonment less cruel, don’t easily exonerate him. Whatever the truth, Roy walked out on a family. Yes, he left behind a sizeable amount of money, enough to make them all comfortable for many years. But he walked out.

My grandfather never expected me to meet the family he left behind in Assam. He kept them secret, and was apparently ready to take the fact of their existence to the grave. It wasn’t until the final decade of his life – through a quite astonishing confluence of a found letter, and my mother’s determined curiosity; another story to be told elsewhere – that his secret legacy was revealed. When he passed away, my mother journeyed back to meet Robin and Sanju, her half-brothers, for the first time. Together, they scattered half of Roy’s ashes in the Brahmaputra, that great and vast river in which he had loved to fish. (The other half went into the soil of Dorset.)

"My grandfather never expected me to meet the family he left behind in Assam. He kept them secret, and was apparently ready to take the fact of their existence to the grave."

I received the part of his life he denied them. Roy returned to England when I was a baby, and I was 18 when he passed away. I was a self-centred adolescent, incapable of thinking that old people were of any interest whatsoever, so I never asked him a single real question. From a few strange ornaments in his flat – including a leopard skin complete with bullet hole, and the kukri knife, its blade mottled with age – I had some vague idea that he had once lived somewhere exotic. But that was the extent of it. According to the obituary written by my step-grandfather, Roy was “a quiet, organised, very private person – except perhaps when he had had a jar or two – who never boasted but was honest and very loyal”. I wouldn’t know; I had no real human impression of him at all. If anything, I thought he was a little uncool, because he once asked me turn down Jimi Hendrix; and I found it bizarre and a little disconcerting that he ate raw chilis and mango pickle with every meal, even breakfast. Beyond this, I barely paid attention. My disinterest has matured into regret, partly as a grandson, partly as a writer.

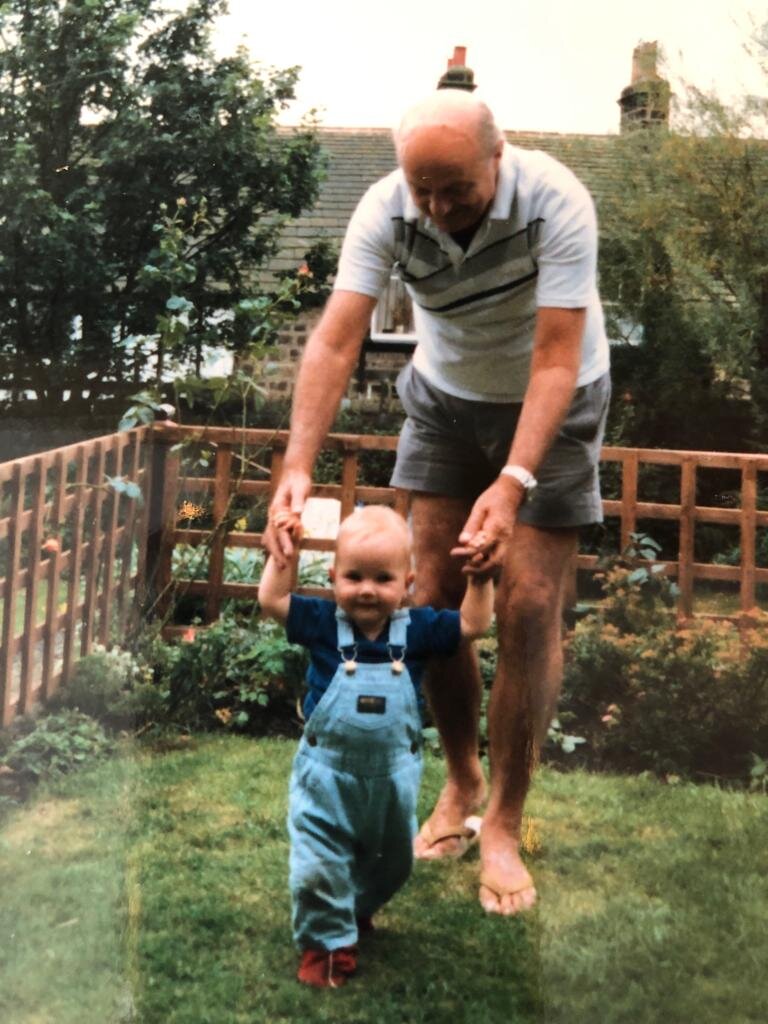

I do remember that he was around the house a lot during a couple of summers, usually in our lounge, long-limbed in an armchair, dozing through a Test match in which Nasser’s England were invariably being trounced. And this is the heart of it: all of my memories of him are filtered through the lens of cricket. All of them. Up until around the age at which one discovers girls and intoxicants, I was an okay cricketer. I captained my town, and had an unsuccessful trial for Sussex. I remember my grandfather at my games: a gently prowling presence, slouched for spells in a camping chair, usually alone, an outstretched leg away from the boundary. Enormous floppy hat covering his bald head, family golden retriever spread at his feet. In the heat he’d undo his shirt and his chest hair was a dazzling white against the deep brown of his skin, leathered from decades of Assamese sun. He helped me with my chin strap once. I remember an umpire asking him to move because he was sat in front of the sightscreen. Another time, I recall him collecting a ball that had gone for four, and not having the shoulder to throw it back anymore, instead rolling it toward the nearest fielder (me, in the invincibility of the teenage body, thinking it incomprehensible that a shoulder could not be capable of throwing). Slim fragments of memory, no wise cricketing aphorisms dispensed as I stepped over the rope – but he was often there, watching.

My uncles have told me that one of their few lasting memories of Roy is him teaching them the basics of cricket in a field behind the house in Assam. It’s about the last thing the oldest of the brothers, Robin, recalls. Big hands over smaller hands around the handle. The wicket-keeper stands here; next to him are what we call the slips. You’re also out if you hit the stumps with your own bat. Your foot can’t cross this line when it’s your turn to bowl. The first time I visited, in 2011, I took the boys a brand new ball, a proper Dukes, as shiny and as red as a beating heart. From the back seat of the car I watched Robin turning it over, lazy snap of his hand, an off-breaker waiting idly for his next delivery, the seam a quivering white line in the air. I thought that my grandfather would never have seen this, seen how well his grown son could turn his wrist over. That was his choice. But he would’ve liked it. A few days later, in a crammed hall up at Monabarie, myself and the sons he never expected me to meet watched Dhoni’s World-Cup-winning six arc toward the smog-smeared Mumbai moon. Delirium in all the local languages. For a moment I loved India as purely as I have ever loved England. Afterwards, up at Roy’s old bungalow – where his name is still up on the wall, commemorating an enormous mahseer he pulled out of the Brahmaputra – we drank enormous amounts of gin, and we didn’t discuss the dead.

"A few days later, in a crammed hall up at Monabarie, myself and the sons he never expected me to meet watched Dhoni’s World-Cup-winning six arc toward the smog-smeared Mumbai moon."

My grandfather is a ghost, but they’re my family now. I travel across half the earth to see my uncles, to split pomegranates with their children, to meet their brilliant wives, to fall asleep to the symphony of dogs quarrelling and geckos calling that must have been strange to Roy too, in the beginning. On my most recent visit, after the morning rain had lifted and the surly cockerels had ceased, I bowled a few loopy ones. My uncle Sanju slapped them into the lemon trees at the edge of the tea plantation. This the same patch of earth where, 40 years ago, he taught them cricket’s basics; basics which will never change. In the evenings we watched the IPL, a format that would have baffled my grandfather, with Bina dashing out during ad breaks to fetch us plates of grilled paneer dripping in awesome amounts of ghee, all of it a product of the household cows. Another morning we left the shade of a vast Banyan tree on a small boat to idle the day away on a small island; while we were there, we mulled on the Indian middle order ahead of the World Cup. I chewed betel nut; I spat it into the river; they laughed. Our lives are passing too, and though our encounter has exotic beginnings, now it is just like any other human bond; that creeping, hungry fondness for both the obvious and the obscured things of a person.

It wouldn’t be right to thank my grandfather for all this; it wasn’t his design. It happened in spite of his secrecy. And yet might the confluence not cheer him, beyond the grave? Mustn’t it have broken the heart even of this private and unflinching man, to leave this corner of India, after 40 years? Morning after morning he woke to the building heat and the eager sounds of life in the seething trees, accumulated those repeated, simple moments that put a place into our blood. The mountain alphabets lived under his tongue; can he ever have stopped being stunned by the majesty of the June rains, so loud that you can’t hear yourself sing? Or by the sight of elephants, old gods of Assam, casting their happy-sad gaze down the riverbank? And after decades of the land, a family. He loved them, of course he loved them. He never said a word, that was him; but something of him surely shrivelled on that last flight out of Calcutta. The boys had his eyes. Have his eyes.

Though he departed Dorset on a coin toss, at 18 years of age, with no special fondness for what back then they still called the Orient, Roy fell for India. And as he fell for India, India absorbed and remade his boyhood sport around him. Cricket was his constant, and by the time he left, he was failing a sort of inverse “Tebbit test”. He wanted to watch Tendulkar bat for as long as possible, even if it was an English attack trying to nick him off. It was India where he most often heard leather meet willow. It was in Assam, not Dorset, that he taught his flesh and blood the basics. Roy’s two worlds and two families – England and Assam – met in the flesh. Might his initial surprise not dissolve into something like familiarity, an impression of essential coherence? Perhaps he doesn’t deserve this happy coda; perhaps it is right that he is deprived of it, having nearly deprived others of it. But what use anger against the mute echo of those who have passed on?

"Roy’s two worlds and two families – England and Assam – met in the flesh. Might his initial surprise not dissolve into something like familiarity, an impression of essential coherence?"

The consciousnesses of Roy, his Assamese family, and his English grandson never shared a space. Time and geography and the grave did for that. I know this, though: all of them loved and love the sight of one ripped through the covers off the fist of the bat. All of them loved and love the death rattle of clean-bowled stumps, the thudding weight of a catch sticking in the palms, the tall shadows of a last hour’s play. These were things of beauty in Dorset in the ’30s, and they’re still things of beauty in a corner of Assam a century on. It is a mystery, really, what these disparate minds shared, where their desires or their fears took or take similar shape. But in each of these private worlds hummed and hums that gentle obsession with the shape and the grace of a half-English, half-Indian game – the only game on earth where you pause to drink tea, that bewitched green leaf without which Roy never visits Assam, without which I am not telling this story.

Most summers, I’ll spend some time in my grandfather’s corner of Dorset; I am here now, tweaking these last paragraphs with the same fussiness that in my teens, while he watched, I used to move third man a touch finer. Dorset is always placid, stupefyingly placid. In the shadow of gnarled cliffs my now-wife and I swim in the breathtaking water, dry on the rocks like seals shocked by the sunshine. Hard to believe there were ever Nazi bombers overhead. In the morning, we watch seabirds slow-wheel over the blinding blue of the Channel, and as we watch them we drink tea – the real stuff, the earthy malty Assam stuff, brought home by the kilogram in brown paper bricks from my uncle Sanju’s garden.

Roy’s old family farm, Wilkswood, is still there today. We swing by; it’s posher than I expected; in the farm shop there are jars of curry sauce and mango chutney. How a world can shrink, in a century. I’d like to bring my uncles to England one day. I’d like to bring them here, to Dorset, this mild and miniature piece of earth that is another planet from India. Maybe the brothers would want to see their father’s grave – a small lichened square of stone sat in the soil of Langton Matravers. Maybe they wouldn’t. That would be up to them.

Riding the trains in India, I have been informed by more than one person that, along with Hindu deities and blood relatives, there is but one acceptable centrepiece for a shrine: Sachin. On the bookshelf in the family home in Assam are two dog-eared copies of his autobiography. Sat round the kitchen table, full of lentils and beer, we watch some YouTube compilations of the old master carving up various hapless bowlers. Here is our easiest language. When he was very near the end, lying skinny and morphined in a hospital bed, my grandfather asked my mother to read him something. By chance, the newspaper she’d bought that morning included a profile of Tendulkar. She read it to him. When she finished, moments before he relaxed out of this life, he said: “Read it again.”